Most Popular Attractions in Myanmar

Yangon – The Most Lively City for Myanmar Tourism

The former capital is one of the most attractive destinations in Myanmar for those who are seeking for a vacation in Asia. Without doubts, Yangon is the most exciting place for Myanmar tourism that opens the opportunity for tourists to admire the most sacred Buddhist pagoda in Myanmar – the elegant Shwedagon pagoda which is gold plated with the diamond studded on top and makes a mystical beauty visible from almost everywhere.

In addition to the charming pagodas, breathtaking landscapes of the city will truly fascinate your senses in your Yangon sightseeing tour. Since it is known as the “Garden of the East”, you should be completely overwhelmed by the landscape of local green lakes, shady parks, and verdant tropical trees. Tired a bit after a long day sightseeing? Markets in Yangon are the paradise that almost makes you swoon! Here you will not only get the chance to enjoy Myanmar authentic specialties but also soak in the Myanmar lifestyle and culture. Bogyoke Aung San Market, Theingyi Zay, China Town, Anawrahta Road are all great and worth exploring. Besides, Yangon brings to you a variety of pleasant hotels and excellent restaurants not inferior to any the other developing cities to sit back. At night, it is a joyful time to indulge in the Yangon nightlife, here blend in and enjoy the vỉbrant atmosphere in a hot nightclub or relax in a tranquil teahouse.

Bagan – The Hidden Treasure in Myanmar

Along with Yangon, Bagan is one of the main tourist attractions in Myanmar. With a repertoire of the massive Buddhist temple, built by King Pagan over many centuries, Bagan is undoubtedly the greatest archaeological site on earth that you should never miss to visit in Myanmar tourism. Nowadays, with 2,220 temples still remaining (in about 13,000 temples in the peak period), this native land unleashes fair chances for you to freely explore Bagan art and architecture by a visit to the Bagan temples. They are close to each other, so it provides you with a wide range of moving ways such as walking, cycling, buses, tuk-tuk or on a hot air balloon to discover this marvelous site. If you have already mesmerized by the ancient architecture of pagodas from the ground, a hot-air balloon flight will provide you a chance to marvel at the wonderful Bagan from above, which is an unforgettable experience. To the southeast of Bagan lies Mount Popa together with a lot of Buddhist monasteries situated. Popa, in Sanskrit, means ‘flower’ as the whole remains are well-known for its breathtaking beauty.

Mandalay – The City of Cultural & Heritage

Located not far from Bagan (about 30-minute flight from Bagan), Mandalay is another beautiful place to visit in Myanmar. Previously, it used to be the capital of ancient Myanmar and now is a city of chaos, smoke, and dust. Whenever you plan for a Myanmar vacation, Mandalay may not the first priority. Nevertheless, just travel here one time, it will never fail to captivate your soul with the majestic beauty of the sacred temples, then you would be definitely amazed by the true beauty of this land when you leave the bustling downtown to visit the architectural wonders. Mahamuni Buddha image, Shwenandaw, Kuthodaw and the complex architecture of Mandalay Hill are the main tourist attractions of Mandalay. Especially, the most prominent site in this city U Bein Bridge which is located in a historic village in Amarapura and considered the longest teak wooden bridge. From here, the most brilliant photography works of sunsets have been being established widely to the world.

Inle Lake – The Breathtaking Lake for Myanmar Tourism

Among the most popular tourist destinations in Myanmar, Inle Lake is the place to be best known by the fishermen with unique fishing methods, just rowing with one leg. Although tourism in the region has developed in recent years, Inle Lake still retains the natural beauty of its capital and one of the main attractions for Myanmar tourism. Getting to Inle, you will experience the sensation of floating houses, an ideal place for you to sink in deeper into this wondrous beauty of nature brings. Along with fishing, traditional handicrafts are a significant part of the local economy, and it’s very intriguing to see silk weavers and silversmiths plying their trade on the lake. As religion plays an integral role in Burmese daily life, numerous pagodas and monasteries can be easily found on the lake and its shores. There are also many restaurants dotted around, where you can indulge in their delicious catches of the day.

Golden Rock Pagoda

Golden Rock Pagoda, also known as Kyaikhtiyo Pagoda is the Myanmar masterpiece ranked third, below only Mahamuni Pagoda and Shwedagon Pagoda. A unique feature of the temple is situated on a protruding rock on a mountain making it a fabulous spot to visit in Myanmar tourism; legend has it that the stone still stands over the years by temples a hair of the Buddha. The strange thing is difficult decoding of the temple, making, even more, mystery and curiosity to many tourists to this place. The Pagoda Festival (also known as the Nine Thousand Lights Festival) takes place at Mount Kyaiktiyo late in the year and participating this event, you will get special food offered by the locals and sightsee the mountaintop fancifully illuminated by candles after dark.

The Ancient City of Mrauk U

Among the best tourist attractions in Myanmar, Mrauk U is the hidden gem that you cannot forget once taking a glance at the fancy mist and smoke in the morning. It is also the 2nd largest center of temples in Myanmar. When you visit it in Myanmar tourism, you will see hundreds of pagodas and temples built of bricks from the 15th century remains, nestled in the hills and small villages. You can also visit the riverside village for a sense of an adventure and enjoy the serenity. Although it is quite hard to get to Mrauk U when you have to embark on a boat to get there, you will be completely fascinated by the labyrinth of maze designed as the tunnels containing the great collection of Buddha statues in Shitthaung Temple, the most impressive relic in this ancient city.

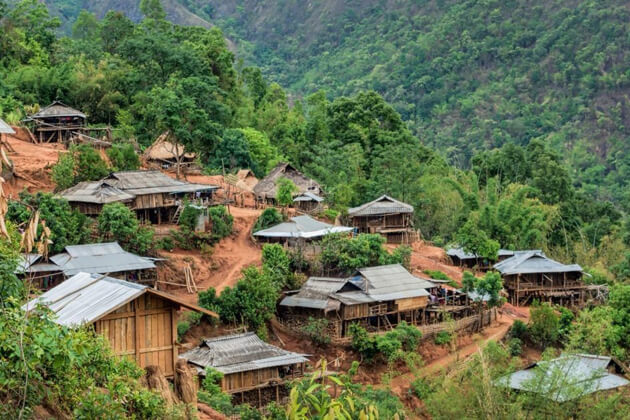

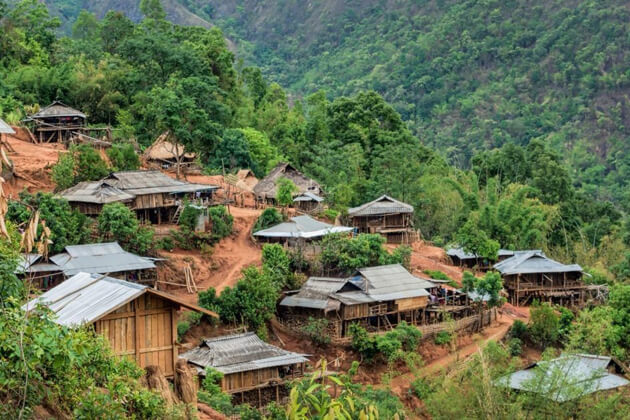

Kengtung (Kyaing Tong)

Kengtung Tong, the capital of the Golden Triangle area, is the beautiful attraction of Myanmar in the far east of Shan State where you are immensely impressed by the beauty of the rolling hills and the idyllic villages. The town is home to numerous Burmese ethnic tribes so it offers you a chance to soak in the cultural diversity of different groups. The arrival point is famous for its picturesque mountains and the ethnic groups living on it as well. This area is quite secluded and remains a vague location with many visitors. If you want a perfect trip here for Myanmar tourism you need to plan well and should go with a local tour guide.

Hpa An

If you are in your Yangon tour, you had better manage to head off the tiny Hpa An town to get the unforgettable experience of a place on Myanmar tourism’s must-see list. Located in the southeast of Yangon, it takes about seven hours in the cart reach here. A short visit to the morning market in downtown Hpa An is an exciting experience to see colorful vendors, stalls with full of products blending with the bustling sounds of local people.

Furthermore, Hpa An is surrounded by dramatic limestone mountains ranges to explore and a great place for a short journey to embark on a ferry drafting along the river to behold the spectacular mountains and serene beauty on the riversides as well. Outside the city is the beauty of the vast green rice fields, with the mountains behind the stone will give you a beautiful sight. There are also lots of temple caves with unique architecture, layout and the people using as the natural Buddhist temples. Getting to know Mount Zwegabin, you may want to conquer its summit to reach the medieval monastery and contemplate the fantastic views of the whole surroundings and plains.

Putao

Putao has been seen as the gateway to climb the mountain ranges of Himalayas for a long time. This is a very familiar place with those people wants to try at climbing in Myanmar tourism. This area has the richest biological diversity in the world, with an average of 30 to 40 new species of flora and faunas discovered each year. Therefore, if you are adventurous, Putao is an ideal choice for you to fall in line. There is nothing better than the experience exploring forests, mountains, river rafting, and massage and then enjoy a delicious cocktail after a long day.

Ngapali & Ngwe beaches

Ngapali is one of the most beautiful tropical beaches on the Bay of Bengal suiting for leisure travel in Myanmar tourism. Situated on the coast of Bengal Bay in Rakhine State, the main feature of this destination is an idyllic stretch of endless white sand and the coastline of palm trees, with a number of resorts beside traditional fishing villages. Another thing that makes Ngapali become a favorite site for Myanmar tourism is the seafood here is really delicious that is highly marked by visitors. You should be absolutely delighted when trying local amazing dishes such as fried squid, lobster, snapper, barracuda, king prawns, and fish curries. You can now move to the beach for a vacation Ngwe beach with limited budgets, where the relatively unspoiled beaches will be very suitable for tourists who prefer the quiet, in a frame of the romantic scene.

Bago

Located 80 kilometers Northeast of Yangon, near Bago River, Bago is an ancient capital of Myanmar, appearing to be a land of myth and legend. At a height of 115 meters, the Shwe Mawdaw Pagoda or Golden God Temple here holds the record for the tallest pagoda in the country. Along with Shwemawdaw, a number of the other large and small pagodas contributes to the well-known abundance of Bago’s religion. Besides, the activities of the morning market near the river and cycling around Stupas and Buddhas make the itinerary worth trying once in Myanmar tourism.

Kalaw – Best Trekking Spot for Myanmar Tourism

Kalaw is a hill station situated about 1300 meters above the sea level. Like the other attractions of Myanmar, you are provided with a wide range of specialties, accommodations, and kinds of entertainment at a reasonable cost. One reason why Kalaw becomes a travel attraction for Myanmar tourism is tourist prefer coming here for trekking. You can independently do a short walk around the area to witness the daily life of the tribal group or discover the mystery of Hnee Pagoda in a cave filled with golden Buddhas. Otherwise, you can rent local guide to go long-way hiking from here to other tourist attractions in Myanmar and perhaps on your way you may catch sight of fascinating heritages remaining from the colonization of Britain.

Bhamo (Bamaw)

Bhamo is a small peaceful town on the banks of the Irrawaddy River in southern. From other parts of the country, most tourists find information and get here by plane. Unless you are unhealthy, you should give it a shot to travel by boat on a picturesque journey along the river to reach this place. Bamaw itself is not glamorous but a pleasurable town to settle and chill out in Myanmar tourism. You may comfort yourself here thanks to warm-hearted residents and a scenic view of the local bamboo bridge.

by.Myanmar Tours